How did you get started with 3D printing at SIMU?

The idea of including a 3D printing lab as part of the Simulation Centre existed from the very beginning, but it wasn’t a priority. Once we had the technology in place and the teaching programs running, my colleague Michal Šemora began experimenting with 3D printing — initially just out of curiosity, printing small objects like stands and learning the technology. Over time, we started producing replacement parts that were frequently lost or damaged. These were still simple items, but already useful in teaching, so we began to feel that we were contributing something meaningful. About a year and a quarter after the Simulation Centre opened, we began developing plans to print models based on real medical data. Since that required a structured approach, we turned it into a formal project. Although we came up with it only three weeks before the submission deadline, it received excellent evaluations.

What were your main goals?

Internally, we wanted to master the technology — learning how to segment CT scan data, later experimenting with 3D scanning (for example, of bones from our Anatomy Department), and generally delving into the possibilities of 3D printing. Externally, our aims were to support our simulation technicians and, through networking, build a community of people interested in applying 3D printing to simulation medicine. Finally, we wanted to create a public portal, which now offers over seventy anatomically accurate models available for anyone to download and print free of charge. Each model comes with a methodology, so even primary schools can use them, not just universities. And we already have more models ready to upload.

Did you know there was demand for anatomical 3D models, or did you create that demand yourselves — from clinicians, teachers, or even primary schools?

I was previously involved in establishing the Pevnost poznání (Fort of Knowledge) science museum in Olomouc, so I knew there was strong public interest in this kind of project. In fact, we presented our project to children at a summer camp there, and their enthusiasm was tremendous. We see it as a combination of popularizing 3D printing and promoting medical science. Gradually, demand began emerging from academic and professional circles as well. We’ve already organized several workshops, both in the Czech Republic and abroad. Recently, I was invited to the European Congress of 3D Printing in Medicine, which helped us raise awareness not only of our project but also of the Faculty of Medicine and the Simulation Centre itself.

There are already portals offering 3D printing models, though their quality varies, and realistic anatomical models can cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Where did you draw inspiration for your own portal?

We’re well aware we’re not the first to think of this. So we tried to find an added value — namely clarity and, most importantly, guaranteed anatomical accuracy. I know of one American portal that’s huge but quite chaotic. At the same time, I’m not aware of any platform focused specifically on simulation medicine. Even when anatomical models are available online, there’s often no guarantee of accuracy. In our case, each model is verified by both anatomists and clinicians before being published.

Where do you get the data for your models?

There are two main sources: CT scans and 3D scans. We 3D-scan materials from our Anatomy Department — for now mainly hard structures, such as bones. The CT data come from the ReDiMed project, of which we are a part.

What can people currently find on the portal, and what do you most often print at SIMU besides bones?

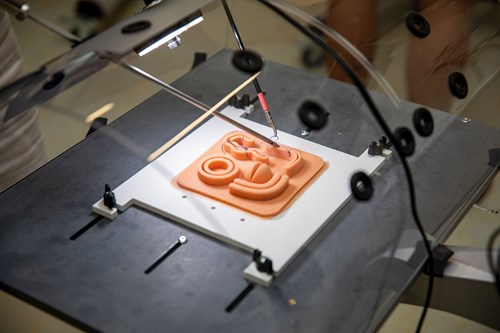

In simulation medicine, soft models are far more interesting — ones that can be cut, sutured, and otherwise manipulated during training. So we often print molds that we then use to cast such models from silicone or foam. The models on the portal are grouped into collections and are quite diverse. We didn’t want to restrict our project partners with strict definitions, so we gave them freedom to focus on what they knew best. For example, we collaborated closely with our Anatomy Department and Surgical Clinic, which is why many of our models are bones. Our colleagues from Germany, on the other hand, had close ties to a pediatric department and contributed many neonatal models. We even have some unique ones — like a sawn skull from the Napoleonic era.

Do you plan to expand the collections further?

Absolutely. Now that the portal is live, it would be a shame to let it stagnate. We enjoy it, and we plan to use it as a platform for uploading our own future models. We’re also bringing in partners — we’ve already been promised models from Motol Hospital in Prague, as well as simple training tools from colleagues in Riga, Latvia. Whenever I present the project, the feedback is positive. Recently, I even received a message from a colleague in Kenya interested in joining. Still, we maintain one rule: every model must have verified accuracy.

How do you select which models to make?

Each model begins with a project guarantor, who identifies a specific need — for example, a colon model for practicing laparoscopic suturing of ruptures. Then we, the technicians, take over the technical production. Finally, the guarantor reviews and approves the model’s accuracy and suitability for its purpose. It’s not just about declaring that a model is anatomically correct — we also need to know in what way it’s correct. For instance, we can create a visually perfect tibia, matching the real bone’s size and even weight, but its material behavior might differ. So we always define the model’s intended use at the beginning — and choose the material density or type of silicone accordingly.

What are the main benefits of in-house 3D printing?

The biggest advantages are self-sufficiency, sustainability, and cost reduction. Producing our own models as needed means we don’t have to keep large inventories. Some training tools we can produce for a fraction of the commercial price, and we can also design custom models tailored to the specific needs of our instructors — even ones that aren’t available on the market at all.

How tempting is it to move beyond educational models?

Our ultimate goal is to apply our 3D printing expertise in clinical medicine. We’ve already started collaborating with colleagues from St. Anne’s University Hospital, focusing on tibial and clavicle fractures. For complex cases, we can print a mirror-image bone based on CT scans of the healthy side, allowing surgeons to pre-plan the operation — positioning titanium plates and screws, testing where to drill, or shaping fixation plates. We handle the technical aspects of the process, while the clinical demand always comes from the surgeons.

What has this project given you personally?

I can honestly say that we’ve significantly advanced 3D printing at our faculty and within the Simulation Centre. We’ve also strengthened our European collaborations. Personally, the project has helped me develop management skills, even though meeting deadlines wasn’t always easy. (smiles)